The ingredients for a successful start-up have been well-covered: A great idea, a large and untapped market, a visionary founding team, an ability to attract talent, great product- and market-execution, and capital efficiency, among others. As a very early-stage investor, and as someone intrinsically attracted to ideas, I spend a lot of time reflecting on whether a young company has a particularly compelling idea. What is the mix of not-too-cold and not-too-hot that makes some ideas seem to burst onto the scene like they’ve always been destined to be a billion-dollar company?

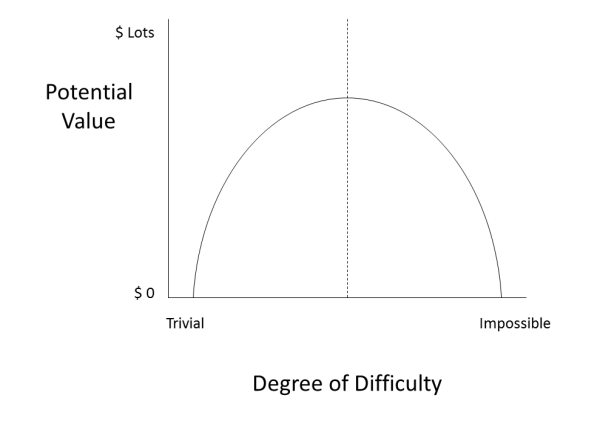

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about just one aspect of a great idea, what I am calling the Start-Up “Degree of Difficulty.” Like in diving and gymnastics, your final score (exit) is a blend of Difficulty and Execution. But unlike in the Olympics, more Difficulty is not always better. Some ideas are just too hard to build into great companies, such as cold fusion and solar concentrators that violate the Second Law of Thermodynamics (sigh.)

The best Degree of Difficulty is that Goldilocks point where a very hard problem can be efficiently overcome by a small, dedicated team who can also erect significant barriers behind them to thwart fast-followers. The trivial ideas are worthless, and so are the impossible visions. (Unless you are Elon Musk, and apparently nothing is impossible.)

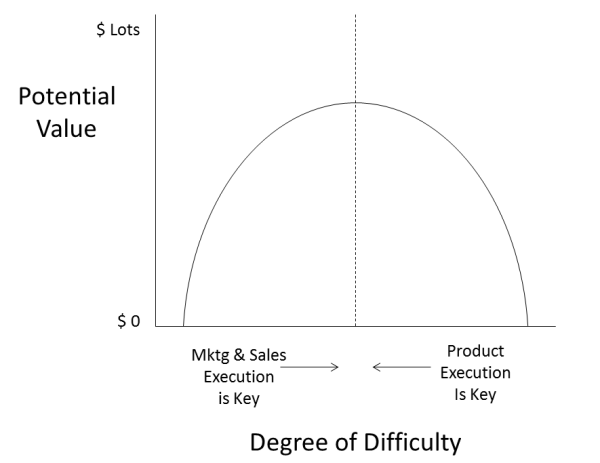

In addition to helping early-stage investors to look for companies in the sweet spot, this framework is useful to remind us what the company’s primary challenge is likely to be. Companies on the the left side can expect a fair amount of competition. Their fate is likely tied (even more so than usual) to exceptionally crisp execution in sales and marketing. Companies on the right side should get more leeway in the marketplace — IF they can get their product to deliver the value they think it can. Their next inflection point comes when they can prove the product is consistently working as expected. These companies might get discontinuous step-ups in valuation around the Series A or B, whereas companies on the left will scale their valuations more smoothly and in step with their market success.

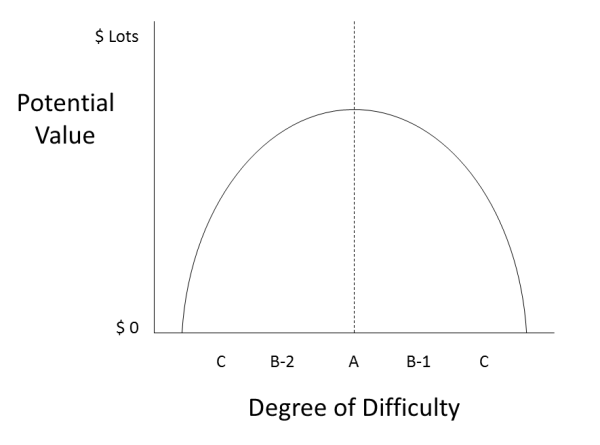

It is useful to know what kind of company investors will perceive you as. And it is useful to know what kind of investor you are looking for! For instance, I have always had a weakness for hard ideas, frequently to my detriment. (e.g., A scripting language for cyber security, Automatic creation of semantic smart links, The aforementioned solar company.) [Please note the grit it takes to link to a reporter’s snarky review of your own worst professional mistake.]

Nonetheless, I continue to like to err on the side of the hard idea. In part because (despite some big failures) I still believe I can assess a good idea better than I can predict a company’s future sales and marketing skills. And if we get the idea and product mostly right, we will have a defensible space from which to iterate on our sales and marketing tactics. I am looking for companies of type A, but when in doubt, I will frequently (though not always) err on the side of type B-1, over type B-2. We should all try to avoid investing our cash or sweat-equity in type C’s.

Note that the y-axis is labeled “Potential Value,” not “Guaranteed Exit Value.” Recall that this whole framework of Degree of Difficulty is just one subset of evaluating the Idea, which itself is one of five or six majority categories that go into a start-up’s likelihood of success. Plenty of companies will fall off this curve. It isn’t clear that Nest, Instagram, WhatsApp or Mandiant rise to the level of B-2 in Difficulty, but they found billion-dollar exits through viral consumer growth or fitting a key strategic need for an industry leader. Conversely, Tesla should have died three times, but Elon Musk seemingly willed it to a $30 billion market cap through his personal grit and bank account. Very likely team, timing, and sheer luck matter more than the idea itself, not to mention the Difficulty of the idea. But all else equal (it never is), I’d like to be invested in the ideas that fit this framework, not try to break it.

Besides, isn’t early stage investing supposed to be fun and a little bit intellectually stimulating? If we are going to do anything as early stage investors other than instantly back the next wunderkinds out of Twitter (team), try to find rocketships just as their traction metrics are taking off (timing), or Spray-and-Pray (luck), shouldn’t we be trying to evaluate an idea’s ability to generate a billion-dollar business? We’ll be basing this mostly on what we’ve seen and worked on before, and that is what this Difficulty Framework is intended to facilitate.

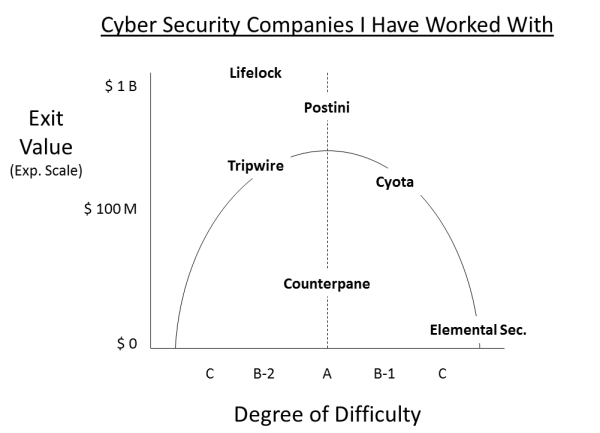

So without further ado, next I plot select Cyber Security companies I have worked with in the past onto the framework.

Instantly we see these six companies do not easily fit the curve. Still, there are some useful anecdotes.

Type C: Elemental Security. Brilliant and visionary, Dan Farmer’s idea was to create a scripting language that could translate English-language descriptions of security needs into automatic administration of a network environment. He even recruited Guido Von Rossum, the creator of Python to the team. Python is now the de facto scripting language for security administration. There are a lot of things we could have done better, but in the end, the vision was probably just too big to practically implement in the time frame you need to succeed as a start-up.

Type B-2: Tripwire‘s initial product was fairly simple, but the company grew quickly because of a product vacuum in the market. I have marked the sale to a private equity firm here, but after some M&A, Tripwire recently “exited” again for $710m. Lifelock was and is a sales and marketing machine, driving it to today’s $1.4 billion market cap.

Type A: What can you say about Counterpane? It was a perfect idea. It did not have a large exit. But it created out of thin air the MSSP market, projected to be a $15 billion market next year. Some execution issues, but also a lot of bad timing and luck. Conversely, Postini simply went on a tear from 2003 to 2007. After several years of modest growth as hosted anti-virus (a decidedly type B-2 idea), Postini hit their stride after pivoting to hosted anti-spam. Spam was exploding, and companies were just beginning to be ready to move key functions to the Cloud. (Salesforce.com revenues in 2003 were $51m compared to a projected $5.4 billion this year.) Everything came together for the most rapid at-scale revenue growth I have been a part of.

Which brings me to Type B-1, which is what I really want to explore. Cyota tackled a problem that in many ways was much harder than Postini’s. Cyota wanted to help protect customers from phishing attacks, however they were launched. Think about the inherently larger scope of that idea. When Postini sold (say) Citibank, they had to parse all of Citibank’s incoming emails. One beauty of the model was how narrow this scope is — just edit your MX records to send us all your incoming email! But when Cyota sold Citibank, they had to try to protect all of Citi’s tens of millions of customers from getting duped in all of cyber space! Of course they had to keep malware off Citibank.com. But they also had to find and neutralize Citibanc.eu, Citi-bank.biz, etc., etc. And they had to try to filter out emails from all of the internet to all of Citibank’s customers with suspicious links. It’s a much bigger problem. In the end, Cyota did this well, if not perfectly (who could?) As such, they got a quick and very healthy acquisition offer from RSA. (Cyota had a truly outstanding team. One board member now runs RSA, and the CEO practically runs Israel.) For our framework, it is noteworthy that as far as I know, Cyota generated the only venture return from that cohort of anti-phishing companies. Whereas anti-spam generated over half a dozen phenomenal venture exits. This is the value of finding the type A idea.

With more advanced phishing on the rise, a new cohort of anti-phishing companies is seeking new successes. One of these within the Cyber Corridor is ZeroFox in Baltimore, backed by NEA and several prominent cyber security individuals including Enrique Salem and John Jack. I had thought “Social Media Security” was a bit trendy and nichy, until I had the pleasure of meeting their COO and speaking in greater depth with their head of product at the RSA Conference. “Social Media Security” doesn’t mean just protecting the social media accounts of Citibank — although it is that. It means finding and neutralizing @citibanc-eu and Facebook.com/citi-bank. It means protecting all of Citibank’s customers from social media hacks that try to play on Citibank’s strong brand in all current social media channels, and all the emerging ones too. To me this is so evocative of Cyota’s goals, I had to create an entire framework to discuss why I am excited about this idea.

ZeroFox has a significant challenge, but they have been tackling it for a few years now. If they can continue to execute on their product vision, I expect they will have substantial elbow room in the marketplace for years to come. But you know me, I am an Ideas-First / B-1 Type guy. Check out the company — and if relevant for you, the service — and decide for yourself.

[…] As I explained back in May, this is what was fascinating about Cyota (acquired by RSA) and ZeroFox (funded by NEA.) They help customers secure not the finite space of their own networks, but the near infinite space of all of cyberspace. Or at least try to. Or at least provide a better, systematic approach to that problem. There is no “perfect security” in these scenarios (or others!), but alternatively the bar is set so low by current “best” practices, these companies can add a lot of value, even early in their product life cycles. […]

LikeLike